Exploration for hydrocarbons and their development has become more challenging with each passing decade. Play fairways are more remote, trapping scenarios more complex, reservoir presence and petrophysical characteristics are more difficult to predict with certainty.

Understanding the geology of the areas of interest becomes more important than ever. The depositional architecture of the sedimentary environments, facies distribution, tectonic evolution and diagenetic history all have an impact on hydrocarbon volume and flow potential.

We attempt to reach this knowledge by combining traditional geological analysis and modern technology in order to produce robust models that can help in the exploration for new prospects, field development plans and identification of infill opportunities in mature fields.

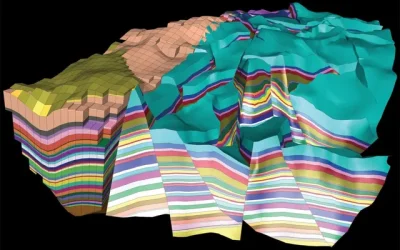

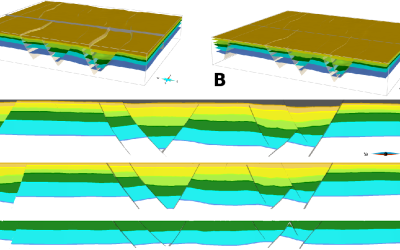

Geological geomodelling is the process of creating a digital representation of the subsurface geology, which includes the spatial distribution of different rock types, faults, fractures, stratigraphy, and other geological features. It is an essential tool in fields like oil and gas exploration, mining, hydrogeology, and environmental science, helping to understand and predict the behavior of the Earth’s subsurface.

Key Components of Geological Geomodelling:

1. Data Integration:

– Geological Data: Information from outcrops, core samples, and geological maps.

– Geophysical Data: Seismic surveys, gravity, and magnetic data.

– Borehole Data: Logs and well data from drilling operations.

– Remote Sensing Data: Satellite images and aerial photos.

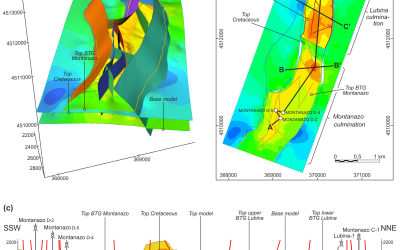

2. Structural Modelling:

– Faults and Fractures: Mapping and modeling of fault planes and fracture networks.

– Stratigraphy: Layering of sedimentary rocks and their relationship over time.

– Topography: Surface elevations and the impact on the subsurface.

3. Petrophysical Modelling:

– Rock Properties: Porosity, permeability, and other properties essential for understanding fluid flow in reservoirs.

– Lithofacies Modelling: Distribution of different rock types or facies within the geological layers.

4. Simulation and Analysis:

– Flow Simulation: Predicting the movement of fluids (oil, gas, water) through the subsurface.

– Reservoir Modelling: Estimating the size and quality of hydrocarbon reservoirs.

– Risk Assessment: Evaluating uncertainties and risks associated with the geological model.

5. Visualization:

– 3D and 4D visualization tools are used to view the geological model, analyze its features, and communicate findings to stakeholders.

Applications:

– Oil and Gas Exploration: Identifying potential hydrocarbon reservoirs and planning drilling operations.

– Mining: Locating and evaluating mineral deposits.

– Groundwater Management: Understanding aquifers for water supply and contamination studies.

– Environmental Studies: Assessing the impact of human activities on subsurface conditions, such as CO2 sequestration or waste disposal.

Techniques and Software:

– Software: Popular geomodelling software includes Petrel (by Schlumberger), GeoModeller, GOCAD, and Surfer.

– Techniques: Methods like kriging, variography, and stochastic simulation are used to interpolate and predict geological features in areas with sparse data.

Geological geomodelling plays a crucial role in making informed decisions about resource extraction, environmental protection, and land use planning by providing a detailed understanding of the Earth’s subsurface.

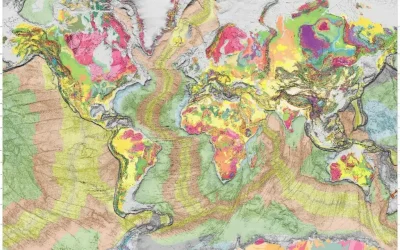

Geological basin analysis is a comprehensive study of sedimentary basins that aims to understand their formation, evolution, and the processes that have shaped them over time. This analysis is crucial for various applications, including hydrocarbon exploration, groundwater management, and understanding Earth’s history. The analysis involves integrating multiple geological, geophysical, and geochemical data sets to create a detailed model of the basin.

Key Components of Basin Analysis

1. Structural Analysis:

– Tectonic Setting: Understanding the tectonic regime (e.g., rift, foreland, intracratonic) that controlled the basin’s formation.

– Faulting and Folding: Analysis of the structural features like faults and folds that affect basin architecture.

– Subsidence History: Investigating how and why the basin subsided over time.

2. Stratigraphic Analysis:

– Sedimentology: Study of the sedimentary rocks to understand the depositional environments (e.g., fluvial, deltaic, marine).

– Sequence Stratigraphy: Analyzing the arrangement of sedimentary layers and understanding the sea-level changes, sediment supply, and tectonic activity.

– Lithofacies and Biofacies: Identifying different rock types and fossil assemblages to interpret past environments.

3. Geophysical Analysis:

– Seismic Data: Using seismic reflection and refraction data to image subsurface structures.

– Gravity and Magnetic Surveys: Analyzing variations in Earth’s gravity and magnetic fields to infer basin structure and composition.

– Well Log Data: Interpretation of borehole data to correlate subsurface layers and identify resources.

4. Geochemical and Petrophysical Analysis:

– Source Rock Analysis: Determining the potential of sedimentary rocks to generate hydrocarbons.

– Thermal Maturity: Assessing the temperature history of the basin to understand the timing of hydrocarbon generation.

– Reservoir Characterization: Evaluating porosity, permeability, and fluid content to assess potential reservoirs.

5. Paleogeographic and Paleoclimatic Reconstruction:

– Paleogeography: Reconstructing the past geographical settings of the basin to understand sediment sources and depositional environments.

– Paleoclimate: Analyzing climate indicators within the basin’s sedimentary record to understand past climate conditions.

6. Basin Modeling:

– 1D, 2D, and 3D Models: Creating numerical models to simulate basin evolution, including sedimentation rates, thermal history, and fluid flow.

– Predictive Modeling: Using models to predict the location of hydrocarbons, minerals, or groundwater.

Applications of Basin Analysis

– Hydrocarbon Exploration: Understanding where oil and gas might be found by identifying potential source rocks, reservoirs, and traps.

– Mineral Exploration: Locating mineral resources associated with sedimentary basins, such as coal or evaporites.

– Groundwater Management: Assessing the quantity and quality of groundwater resources within a basin.

– Environmental Studies: Understanding the geological history for better environmental planning and hazard assessment.

– Academic Research: Contributing to the broader understanding of Earth’s geological history, tectonics, and climate changes.

Methods and Techniques

– Field Mapping: Direct observation and sampling of rocks exposed at the surface.

– Remote Sensing: Using satellite imagery to map and analyze large-scale geological features.

– Geochronology: Dating rocks and minerals to determine the timing of basin-related events.

– Petroleum System Modeling: Integrating geological, geochemical, and geophysical data to model the generation, migration, and trapping of hydrocarbons.

Challenges in Basin Analysis

– Data Integration: Combining diverse datasets (geological, geophysical, geochemical) is complex and requires careful calibration.

– Uncertainty: Incomplete data and the inherent variability of geological processes lead to uncertainty in models and interpretations.

– Scale Issues: Basin processes operate at various scales, from microscopic pore networks to regional tectonic features, requiring multi-scale analysis.

Basin analysis is a multidisciplinary approach that provides valuable insights into the complex processes shaping sedimentary basins. It is an essential tool in the exploration and management of natural resources.

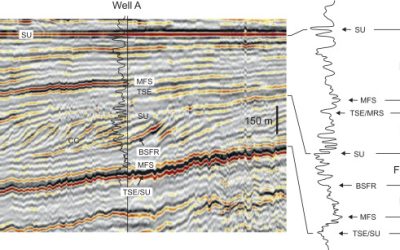

Sequence seismic stratigraphy is an advanced method used in geology and geophysics to interpret the arrangement and history of sedimentary layers using seismic data, particularly in the context of stratigraphic sequences. This approach integrates concepts from sequence stratigraphy with seismic reflection data to analyze subsurface geological structures and sedimentary processes over time.

Key Concepts in Sequence Seismic Stratigraphy

1. Sequence Stratigraphy:

– Sequences: Stratigraphic units bound by unconformities or their correlative conformities, representing cycles of relative sea-level change.

– Systems Tracts: Subdivisions within sequences that reflect specific depositional environments, such as lowstand, transgressive, and highstand systems tracts.

– Parasequences: Small-scale, relatively conformable successions of genetically related beds or bedsets within a sequence, often bounded by flooding surfaces.

2. Seismic Stratigraphy:

– Seismic Reflectors: Continuous, high-amplitude reflections in seismic data that represent boundaries between different sedimentary layers.

– Seismic Facies: Distinct seismic reflection patterns that suggest specific depositional environments or lithologies.

– Reflection Terminations: Indicators of stratigraphic boundaries, where seismic reflections either onlap, downlap, toplap, or truncate against a surface.

Integrating Seismic Data with Sequence Stratigraphy

1. Identification of Sequences:

– Unconformities and Sequence Boundaries: These are identified as major seismic reflectors that represent breaks in deposition or erosion, indicating relative sea-level changes.

– Mapping Sequences: By tracking seismic reflectors across a basin, geologists can map out sequence boundaries and correlate them across different regions.

2. Systems Tracts Interpretation:

– Lowstand Systems Tract (LST): Often identified by seismic onlap patterns, where sediments accumulate during a relative sea-level lowstand.

– Transgressive Systems Tract (TST): Characterized by backstepping reflections, indicating landward movement of shorelines as sea level rises.

– Highstand Systems Tract (HST): Marked by aggradational to progradational seismic facies, where sediment accumulation occurs during stable or falling sea levels.

3. Seismic Facies Analysis:

– Depositional Environment Interpretation: By analyzing the seismic facies (e.g., parallel, chaotic, hummocky reflections), geologists can infer depositional environments such as deep marine, deltaic, or fluvial settings.

– Lithology Prediction: Certain seismic facies patterns can be associated with specific rock types, aiding in predicting subsurface lithology.

4. Reflection Terminations and Stratigraphic Surfaces:

– Onlap: Indicates landward migration of facies, often associated with transgressive sequences.

– Downlap: Reflects basinward progradation of sedimentary deposits, typical of highstand systems tracts.

– Toplap: Results from non-deposition or slight erosion at the top of a sequence, often associated with falling sea levels.

– Truncation: Represents significant erosion, marking major sequence boundaries.

Applications of Sequence Seismic Stratigraphy

1. Hydrocarbon Exploration:

– Reservoir Identification: Helps in identifying potential reservoirs by mapping stratigraphic traps, which are often associated with specific systems tracts.

– Source Rock and Seal Prediction: Sequence stratigraphy aids in predicting the location of source rocks and seals, critical for hydrocarbon generation and trapping.

– Timing of Hydrocarbon Migration: By understanding the sequence of deposition and subsidence, geologists can estimate the timing of hydrocarbon generation and migration.

2. Paleogeographic Reconstruction:

– Mapping Past Environments: Sequence seismic stratigraphy allows for the reconstruction of ancient depositional environments, helping to understand the geological history of a basin.

– Sea-Level Change Analysis: By identifying and correlating sequences across a basin, geologists can infer past sea-level changes and their impact on sedimentation patterns.

3. Reservoir Characterization:

– Predicting Reservoir Quality: Understanding the sequence stratigraphy of a basin helps in predicting variations in reservoir quality, such as porosity and permeability, which are often controlled by depositional processes.

– Facies Distribution: Helps in predicting the lateral and vertical distribution of different sedimentary facies, critical for effective reservoir management.

4. Environmental and Engineering Applications:

– Groundwater Resource Management: Sequence stratigraphy can be used to map aquifers and understand groundwater flow patterns.

– Geotechnical Site Investigation: Helps in assessing the geological conditions of a site, particularly for large engineering projects.

Challenges in Sequence Seismic Stratigraphy

– Resolution Limitations: Seismic data may have limited resolution, making it challenging to identify thin beds or subtle stratigraphic features.

– Data Quality: The quality of seismic data, affected by factors like noise and signal attenuation, can limit the accuracy of stratigraphic interpretations.

– Complex Geology: In areas with complex tectonics or sedimentation patterns, interpreting sequences and systems tracts can be challenging.

Sequence seismic stratigraphy is a powerful tool for understanding the subsurface geology of sedimentary basins. It combines the detailed stratigraphic analysis of sequence stratigraphy with the imaging capabilities of seismic data, providing valuable insights for resource exploration, environmental studies, and academic research.

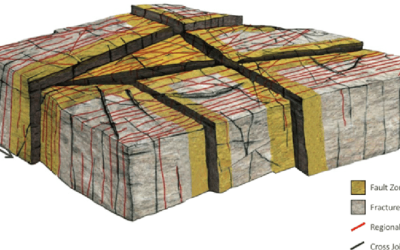

Fractured reservoirs are a type of hydrocarbon reservoir where the primary porosity and permeability are provided not by the rock matrix but by a network of fractures. These fractures can significantly influence the storage and flow of fluids within the reservoir, making their study and understanding crucial for effective resource extraction.

Characteristics of Fractured Reservoirs

1. Fracture Networks:

– Natural Fractures: These are fractures formed due to tectonic stresses, thermal contraction, or other geological processes. They can be highly interconnected, providing pathways for fluid flow.

– Induced Fractures: Often created during drilling or hydraulic fracturing operations to enhance permeability.

– Fracture Types: Includes joints, faults, and veins, which vary in size, orientation, and connectivity.

2. Dual Porosity System:

– Matrix Porosity: The primary porosity of the rock, usually low in fractured reservoirs, provides limited storage capacity.

– Fracture Porosity: Secondary porosity provided by fractures, which often plays a more significant role in fluid flow compared to matrix porosity.

3. Heterogeneity:

– Variable Permeability: Fractured reservoirs are highly heterogeneous, with permeability varying significantly both laterally and vertically.

– Compartmentalization: Fractures can create compartments within the reservoir, leading to isolated pockets of hydrocarbons.

4. Fluid Flow Dynamics:

– Anisotropy: The permeability in fractured reservoirs is often directional, depending on the orientation and density of fractures.

– Flow Channels: Fractures can create high-permeability channels that dominate fluid flow, while the rock matrix contributes to slower, diffusive flow.

Types of Fractured Reservoirs

1. Carbonate Reservoirs:

– Limestone and Dolomite: These are commonly fractured due to their brittle nature and are often associated with significant oil and gas reserves.

– Karst Systems: In some carbonate reservoirs, fractures are associated with dissolution features, enhancing porosity and permeability.

2. Clastic Reservoirs:

– Sandstones: Though typically less fractured than carbonates, certain sandstones may develop fractures, especially in tectonically active regions.

– Shales: Often exhibit micro-fractures, particularly in unconventional reservoirs like shale gas plays.

3. Basement Reservoirs:

– Crystalline Rocks: In some regions, oil and gas are found in fractured crystalline basement rocks, where the fractures provide the primary reservoir space.

Exploration and Development of Fractured Reservoirs

1. Geological and Geophysical Analysis:

– Seismic Data: Seismic surveys, especially 3D and 4D seismic, can help identify fracture networks and their orientation.

– Core and Well Log Data: Core samples and well logs (e.g., FMI, FMS) provide direct evidence of fractures and help in characterizing their properties.

– Fracture Modeling: Using geological models to predict the distribution and impact of fractures on reservoir performance.

2. Reservoir Engineering:

– Simulation Models: Reservoir simulators incorporating dual-porosity or dual-permeability models help predict fluid flow in fractured systems.

– Well Placement: Optimizing the location and orientation of wells to intersect major fracture networks, enhancing hydrocarbon recovery.

– Enhanced Recovery Techniques: Hydraulic fracturing or acidizing treatments are often used to increase connectivity and improve production rates.

3. Production Challenges:

– Water Production: Fractures can provide rapid pathways for water from underlying aquifers, leading to water production issues.

– Pressure Management: Managing reservoir pressure is crucial in fractured reservoirs, as fractures can cause rapid pressure declines.

– Variable Recovery: Due to the heterogeneity and compartmentalization, recovery rates can vary widely across the reservoir.

Importance of Fractured Reservoirs

– Significant Hydrocarbon Source: Fractured reservoirs represent a substantial portion of the world’s oil and gas reserves, particularly in regions like the Middle East, North Sea, and parts of the United States.

– Unconventional Resources: Fractured reservoirs include unconventional plays such as shale gas, tight oil, and geothermal resources.

– Complex Reservoir Management: The complexity of fractured reservoirs requires advanced techniques and technologies for successful exploration and production.

Challenges in Fractured Reservoirs

1. Complexity in Characterization:

– Fracture networks are difficult to predict and model, requiring extensive data collection and sophisticated modeling techniques.

2. Uncertainty in Production:

– Production rates can be unpredictable due to the variability in fracture connectivity and the potential for compartmentalization.

3. Enhanced Recovery Difficulties:

– Techniques like waterflooding or gas injection may be less effective in fractured reservoirs due to rapid breakthrough or uneven distribution of the injected fluids.

4. Environmental and Operational Risks:

– Hydraulic fracturing, commonly used to enhance production, has environmental concerns, including induced seismicity and groundwater contamination.

Conclusion

Fractured reservoirs present unique challenges and opportunities in the field of petroleum geology and engineering. Understanding the fracture networks, their impact on fluid flow, and how to effectively model and manage these reservoirs are crucial for optimizing hydrocarbon recovery and ensuring sustainable resource development.

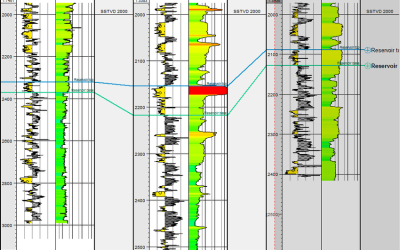

Well correlation is a fundamental technique in petroleum geology and reservoir engineering, used to correlate and correlate stratigraphic units between different wellbores. This process is critical for understanding the subsurface geology, mapping reservoir extent, and making informed decisions about hydrocarbon exploration and production.

Objectives of Well Correlation

1. Stratigraphic Correlation:

– Identifying Stratigraphic Units: Correlating rock layers across wells to identify equivalent strata and understand the lateral continuity of geological formations.

– Mapping Reservoir Extent: Determining the distribution and thickness of reservoirs, source rocks, seals, and other key stratigraphic units.

– Understanding Depositional Environments: Interpreting changes in depositional environments and their impact on reservoir quality.

2. Structural Correlation:

– Fault Identification: Identifying and mapping faults by recognizing vertical or lateral offsets in correlated strata.

– Structural Mapping: Constructing subsurface structural maps that show the geometry and distribution of geological features like folds and faults.

3. Reservoir Characterization:

– Fluid Distribution: Correlating fluid contacts (e.g., oil-water, gas-oil contacts) between wells to understand fluid distribution within the reservoir.

– Petrophysical Properties: Correlating well logs to identify variations in porosity, permeability, and other reservoir properties.

Key Data Sources for Well Correlation

1. Well Logs:

– Gamma Ray (GR): Commonly used for identifying lithology and correlating shale versus sand layers.

– Resistivity Logs: Used to identify hydrocarbon-bearing zones and correlate fluid contacts.

– Density and Neutron Logs: Provide information on rock porosity and help distinguish between different lithologies.

– Sonic Logs: Used for identifying stratigraphic boundaries and lithological changes.

2. Core Data:

– Core Samples: Provide direct physical evidence of rock types and can be used to validate well log interpretations.

– Core Analysis: Detailed analysis of core data (e.g., porosity, permeability) can be correlated with well logs to improve subsurface models.

3. Cuttings and Mud Logs:

– Cuttings: Rock fragments obtained during drilling, analyzed to identify lithology and correlate with well logs.

– Mud Logs: Provide real-time information on lithology and gas shows, useful for initial correlation during drilling.

4. Seismic Data:

– Seismic-to-Well Tie: Correlating seismic data with well logs to extend well correlations across larger areas where no wells exist.

– Synthetic Seismograms: Generated from well logs to help tie well data with seismic reflections.

Steps in Well Correlation

1. Data Preparation:

– Standardize Data: Ensure that well logs are standardized, corrected, and calibrated for consistent interpretation.

– Select Key Wells: Choose a reference well with good data quality to begin the correlation process.

2. Correlation of Major Units:

– Identify Key Markers: Start by identifying major stratigraphic markers, such as unconformities or distinctive lithologic units, that can be correlated across wells.

– Correlation of Primary Units: Correlate primary stratigraphic units or formations between wells, using well logs, core data, and other available data.

3. Correlation of Secondary Units:

– Finer Resolution: After correlating major units, focus on finer stratigraphic details, such as parasequences or individual beds, to achieve higher-resolution correlations.

– Facies Analysis: Incorporate facies interpretation to correlate depositional environments and predict reservoir quality variations.

4. Integration with Other Data:

– Integrate Seismic Data: Use seismic data to validate and refine well correlations, especially in areas with sparse well control.

– Use of Cross Sections: Construct geological cross sections to visualize the correlation and confirm the geological model.

5. Validation and Refinement:

– Cross-Check Correlations: Validate correlations by cross-checking with other wells, seismic data, and geological models.

– Iterative Process: Refine correlations as more data becomes available or as new wells are drilled.

Applications of Well Correlation

1. Reservoir Modeling:

– 3D Reservoir Models: Correlated well data is used to build 3D reservoir models that guide development plans and production strategies.

– Reservoir Simulation: Accurate well correlation improves the quality of reservoir simulations, leading to better predictions of fluid flow and recovery.

2. Field Development Planning:

– Well Placement: Correlation helps in optimal well placement, ensuring wells are drilled into the most productive parts of the reservoir.

– Drilling Strategy: Correlations inform drilling strategies by identifying potential drilling hazards or by planning horizontal wells in thin, laterally extensive reservoirs.

3. Exploration:

– Prospect Evaluation: Well correlation helps in evaluating exploration prospects by understanding the continuity of potential reservoirs between known discoveries and undrilled areas.

– Risk Assessment: By correlating stratigraphic traps or seals, geologists can better assess exploration risks.

4. Production Optimization:

– Enhanced Recovery: Correlation supports enhanced recovery techniques by identifying bypassed pay zones or heterogeneities that impact production efficiency.

– Reservoir Management: Continuous correlation during production helps in monitoring reservoir performance and updating models as new data is acquired.

Challenges in Well Correlation

1. Data Quality and Availability:

– Incomplete Data: Poor quality or incomplete well logs can lead to uncertainties in correlation.

– Sparse Well Control: In areas with few wells, correlations are more challenging and less certain.

2. Complex Geology:

– Structural Complexity: In tectonically active regions, faults and folds can complicate well correlations.

– Stratigraphic Complexity: Variations in depositional environments, rapid facies changes, or erosion can create difficulties in correlating units.

3. Scale Issues:

– Vertical Resolution: Differences in the vertical resolution of different well logs can lead to mismatches in correlations.

– Lateral Variation: Rapid lateral changes in lithology or thickness can make correlation challenging.

4. Human Interpretation:

– Subjectivity: Well correlation is often subjective, relying on the geologist’s experience and interpretation, leading to different possible correlations.

Well correlation is a critical process in subsurface geological studies, providing the foundation for accurate reservoir characterization and effective resource management.

Geological volumetric analysis is a crucial process in the field of petroleum geology, mining, and resource estimation, used to quantify the volume of rock units and the amount of extractable resources, such as hydrocarbons, minerals, or water, within a geological formation or reservoir. This analysis helps in estimating the size of a reservoir or ore body, which is essential for determining its economic viability and guiding development strategies.

Objectives of Geological Volumetric Analysis

1. Resource Estimation:

– Hydrocarbon Volumes: Estimating the amount of oil, gas, or condensate present in a reservoir.

– Mineral Reserves: Determining the volume of ore and the concentration of valuable minerals within a deposit.

– Water Resources: Calculating the volume of water in aquifers for groundwater management.

2. Reservoir Characterization:

– Reservoir Size: Defining the spatial extent and thickness of the reservoir.

– Porosity and Saturation: Estimating the porosity (void space in the rock) and fluid saturation (percentage of pore space filled with fluids) to determine the amount of recoverable resources.

3. Development Planning:

– Well Placement: Informing well placement and drilling strategies based on the estimated size and shape of the reservoir.

– Production Forecasting: Predicting production rates and the life of the reservoir based on volumetric estimates.

Key Components of Volumetric Analysis

1. Gross Rock Volume (GRV):

– Structural Mapping: Creating structural maps of the top and base of the reservoir or ore body to define its geometry.

– Isopach Maps: Generating thickness maps (isopach maps) that show the variation in thickness across the reservoir or formation.

– Calculation: GRV is calculated as the product of the area of the reservoir and its thickness. This provides the total volume of rock within the defined boundaries.

2. Net Reservoir Volume:

– Net-to-Gross Ratio (N/G): The ratio of net reservoir rock (rock that can store fluids or minerals) to the total gross rock volume. This accounts for non-reservoir rocks like shales or non-mineralized zones.

– Net Reservoir Thickness: Calculating the thickness of the reservoir that has favorable properties (e.g., sufficient porosity and permeability) for storing and transmitting fluids or containing minerals.

3. Porosity:

– Effective Porosity: The fraction of the total rock volume that consists of interconnected pore spaces, which can contribute to fluid flow or mineral storage.

– Porosity Estimation: Derived from core samples, well logs (e.g., density, neutron, sonic logs), or seismic data.

4. Fluid Saturation:

– Water Saturation (Sw): The percentage of the pore space filled with water. Lower Sw usually indicates higher hydrocarbon saturation.

– Hydrocarbon Saturation (Sh): The percentage of the pore space filled with hydrocarbons (oil or gas).

– Saturation Determination: Measured using well logs, such as resistivity logs, or derived from core samples.

5. Recovery Factor (RF):

– Definition: The percentage of hydrocarbons or minerals that can be technically and economically recovered from the reservoir.

– Influencing Factors: Depends on the reservoir properties, extraction technology, and economic considerations. For hydrocarbons, factors like drive mechanisms (e.g., water drive, gas cap drive) and enhanced recovery techniques play a role.

6. Volume Calculations:

For Hydrocarbons:

– Original Oil in Place (OOIP)

– Gas Initially in Place (GIIP)

Where:

– A = Area of the reservoir (acres)

– h = Net pay thickness (feet)

– φ = Porosity (fraction)

– Sw = Water saturation (fraction)

– B_o = Formation volume factor for oil (bbl/STB)

– B_g = Formation volume factor for gas (cf/scf)

For Minerals:

– Tonnage Calculation

– Metal Content

7. Economic Considerations:

– Cut-Off Grade: In mining, only ore above a certain grade is considered economic. Similarly, in hydrocarbon extraction, only volumes above a certain recovery factor are considered.

– Price Sensitivity: Volumetric analysis often includes scenarios based on different commodity prices to assess economic viability.

Applications of Volumetric Analysis

1. Hydrocarbon Exploration and Production:

– Field Appraisal: Estimating the size of a new discovery and planning the field development accordingly.

– Reserves Estimation: Classifying reserves as proven, probable, or possible based on volumetric analysis and the certainty of the data.

2. Mining:

– Ore Reserve Estimation: Calculating the volume and grade of ore in a deposit to determine if it can be mined profitably.

– Mine Planning: Designing the mine layout, determining the best extraction methods, and forecasting production based on volumetric estimates.

3. Water Resources Management:

– Aquifer Volume Estimation: Calculating the volume of water stored in an aquifer for sustainable groundwater management.

– Recharge and Withdrawal Rates: Balancing the volume of water withdrawn with natural or artificial recharge rates to prevent depletion.

Challenges in Volumetric Analysis

1. Data Quality and Availability:

– Limited Data: Sparse well control or poor-quality seismic data can lead to uncertainties in volume estimation.

– Variable Data: Different data sources (well logs, cores, seismic) may give conflicting results, complicating the analysis.

2. Geological Complexity:

– Heterogeneous Reservoirs: Variations in rock properties, such as porosity and permeability, can make it difficult to estimate volumes accurately.

– Structural Complexity: Faults, folds, and other structural features can complicate the geometry of the reservoir or ore body.

3. Uncertainty in Parameters:

– Porosity and Saturation Estimates: These parameters are often derived from indirect measurements, leading to potential errors.

– Recovery Factor: Estimating the recovery factor involves assumptions about future production techniques and market conditions, which are inherently uncertain.

4. Economic and Technical Limitations:

– Technological Constraints: The available technology may limit the amount of recoverable resources, affecting volumetric estimates.

– Price Fluctuations: Commodity prices can impact the economic viability of resources, leading to changes in the classification of reserves.

Conclusion

Geological volumetric analysis is a critical step in the evaluation and development of natural resources, providing the quantitative basis for resource estimation and economic evaluation. Despite its challenges, accurate volumetric analysis is essential for making informed decisions in exploration, production, and resource management.

Biostratigraphy is a branch of stratigraphy that uses the fossil content of sedimentary rocks to establish the relative ages of rock layers and to correlate those layers across different geographic areas. It plays a crucial role in understanding the geological history of the Earth, particularly in the context of petroleum exploration, paleontology, and evolutionary studies.

Objectives of Biostratigraphy

1. Relative Dating:

– Determining Relative Ages: Establishing the relative ages of rock layers based on the fossils they contain, without necessarily determining their absolute age in years.

– Temporal Correlation: Correlating rock layers across different regions by matching the fossil content, allowing geologists to create a chronological framework for the deposition of sedimentary sequences.

2. Geological Correlation:

– Regional Correlation: Correlating sedimentary sequences across a basin or region to understand the extent and distribution of rock units.

– Global Correlation: Correlating sequences on a global scale, particularly through the use of index fossils, to connect geological events worldwide.

3. Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction:

– Reconstructing Past Environments: Using fossil assemblages to infer past environments, such as marine, terrestrial, or transitional settings.

– Paleoclimate Indicators: Certain fossils can indicate past climatic conditions, such as warm or cold periods.

4. Evolutionary Studies:

– Tracking Evolutionary Changes: Biostratigraphy provides evidence of evolutionary changes over time, helping to trace the development and extinction of species.

– Biostratigraphic Zonation: Dividing geological time into zones based on the presence of specific fossil assemblages, which reflect evolutionary stages.

Key Concepts in Biostratigraphy

1. Index Fossils:

– Definition: Fossils of organisms that lived for a relatively short period but were widespread geographically. These fossils are particularly useful for correlating rock layers.

– Characteristics: Ideal index fossils are easily recognizable, abundant, geographically widespread, and have a narrow stratigraphic range.

Examples of Index Fossils:

– Ammonites: Widely used in Mesozoic marine rocks.

– Foraminifera: Microscopic marine organisms, especially useful in Cenozoic and Mesozoic stratigraphy.

– Trilobites: Common in Paleozoic rocks.

2. Biozones:

– Definition: Stratigraphic intervals defined by the presence of specific fossil assemblages. Biozones are the basic units of biostratigraphy.

– Types of Biozones:

– Range Biozones: Defined by the total range of a single taxon.

– Assemblage Biozones: Defined by the co-occurrence of multiple taxa.

– Abundance Biozones: Defined by the peak abundance of a particular taxon.

3. Biostratigraphic Correlation:

– Lateral Correlation: Matching rock layers from different locations based on their fossil content to establish equivalence.

– Vertical Correlation: Establishing a sequence of events or relative ages within a single location based on the stratigraphic distribution of fossils.

4. Paleoecology:

– Ecological Preferences: Understanding the environmental preferences of fossil species to reconstruct ancient environments.

– Facies Fossils: Fossils that indicate specific environmental conditions, such as shallow marine, deep marine, or terrestrial settings.

5. Fossil Succession:

– Principle of Fossil Succession: The concept that fossil assemblages succeed one another in a recognizable and determinable order, allowing geologists to identify the relative ages of rock layers.

– Evolutionary Trends: Observing evolutionary changes in fossil lineages through time to refine biostratigraphic zonations.

Applications of Biostratigraphy

1. Petroleum Exploration:

– Reservoir Correlation: Biostratigraphy is used to correlate reservoir rocks across different wells, helping to map the extent of hydrocarbon-bearing formations.

– Stratigraphic Traps: Identifying potential stratigraphic traps where hydrocarbons might be accumulated based on changes in fossil assemblages.

2. Paleontology:

– Fossil Studies: Biostratigraphy helps paleontologists understand the distribution of fossils through time, providing insights into the evolution and extinction of species.

– Extinction Events: Studying mass extinction events and their impact on the fossil record, such as the extinction of dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous.

3. Geological Mapping:

– Stratigraphic Correlation: Mapping rock units across large areas by correlating them using fossil content, which is crucial for creating accurate geological maps.

– Basin Analysis: Understanding the depositional history of sedimentary basins by correlating rock sequences and reconstructing paleoenvironments.

4. Climate Studies:

– Paleoclimatology: Using fossil assemblages to infer past climates and track climatic changes through geological time.

– Sea-Level Changes: Correlating marine fossils with changes in sea level, which can be linked to global climate shifts.

5. Chronostratigraphy:

– Geologic Time Scale: Biostratigraphy contributes to the development of the geologic time scale by providing a relative chronology of rock layers.

– Subdivision of Time Periods: Defining the boundaries of geologic periods, epochs, and stages based on biostratigraphic markers.

Challenges in Biostratigraphy

1. Fossil Preservation:

– Taphonomic Bias: The preservation of fossils is not uniform, leading to gaps in the fossil record that can complicate correlation.

– Diagenesis: Post-depositional processes can alter or destroy fossils, reducing their utility for biostratigraphy.

2. Taxonomic Uncertainty:

– Species Identification: Difficulty in identifying species accurately can lead to errors in correlation and interpretation.

– Synonymy: Different names may be used for the same species in different regions or by different researchers, leading to confusion.

3. Stratigraphic Gaps:

– Unconformities: Erosional or non-depositional periods can create gaps in the stratigraphic record, disrupting the continuity of fossil assemblages.

– Condensed Sections: In areas with slow sedimentation rates, fossil-rich horizons may be condensed, complicating biostratigraphic interpretation.

4. Biogeographic Variations:

– Endemism: Some fossils may be restricted to certain regions, making it difficult to correlate globally.

– Latitudinal Differences: Climate and geography can influence the distribution of species, affecting the consistency of biostratigraphic markers across different areas.

5. Evolutionary Rates:

– Punctuated Equilibria: Evolutionary changes may occur rapidly over short periods, followed by long periods of stability, leading to complex biostratigraphic patterns.

– Gradualism: Slow, continuous evolutionary changes can make it difficult to identify distinct biozones.

Conclusion

Biostratigraphy is a powerful tool for understanding the geological history of the Earth, particularly in terms of correlating rock layers and establishing their relative ages. Despite the challenges, it remains a key method in fields such as petroleum exploration, paleontology, and environmental reconstruction. By carefully analyzing fossil content, geologists can reconstruct past environments, correlate stratigraphic sequences, and track the evolution of life through geological time.

Structural restoration is a geological technique used to reconstruct the original geometry and configuration of deformed geological structures, such as folds, faults, and layers. This process involves “restoring” the geological features to their pre-deformation state to understand the history and mechanics of deformation, predict subsurface structures, and assess the implications for resource exploration, particularly in hydrocarbon and mineral reservoirs.

Objectives of Structural Restoration

1. Understanding Deformation History:

– Chronological Reconstruction: Reconstruct the sequence of tectonic events that led to the current geological configuration.

– Mechanism of Deformation: Analyze the processes (e.g., folding, faulting) responsible for the observed geological structures.

2. Validation of Geological Models:

– Consistency Check: Ensure that the interpreted geological model is geologically feasible and consistent with the laws of physics and geology.

– Balancing Cross-Sections: Ensure that the restored section is geometrically balanced, meaning that no material is created or destroyed in the restoration process.

3. Resource Exploration:

– Predicting Subsurface Structures: Use the restoration to predict the location and geometry of subsurface traps, which may host hydrocarbons, minerals, or other resources.

– Reservoir Quality Assessment: Understand how deformation has affected reservoir quality, including porosity, permeability, and fracture distribution.

4. Paleogeographic Reconstruction:

– Reconstructing Past Landscapes: Restore the pre-deformation topography to understand ancient landscapes, depositional environments, and paleoclimate.

– Tectonic Plate Movements: Infer past tectonic plate movements and interactions based on the restoration of large-scale structures.

Key Concepts in Structural Restoration

1. Deformation Mechanisms:

– Folding: Restoration of folds to their undeformed state by “unfolding” the layers to understand the original horizontal layers and the forces that caused the folding.

– Faulting: Restoring faulted blocks to their pre-faulting positions to reconstruct the original stratigraphy and structure.

2. Restoration Techniques:

– Unfolding: Techniques to “unbend” folded layers, often applied in areas with significant compressional tectonics.

– Unfaulting: Moving faulted blocks back to their original positions, accounting for displacement along the fault plane.

– Decompaction: Restoring layers to their original thickness before compaction due to sedimentary loading, often using porosity-depth relationships.

– Unstretching/Unshearing: Reverse the effects of stretching or shearing, particularly in extensional or transpressional regimes.

3. Geometric Methods:

– Kinematic Models: Models that describe the motion and deformation history of rocks based on observed structures, assuming certain deformation mechanisms.

– Line- and Area-Balancing: Ensuring that the restored section balances in terms of length (1D) or area (2D), implying conservation of mass and volume.

4. Physical Constraints:

– Material Conservation: Ensure that the restoration process conserves the amount of material (no volume loss or gain) unless specific geological processes (e.g., erosion or deposition) justify otherwise.

– Stratigraphic Integrity: Ensure that stratigraphic relationships (e.g., relative ages of rock units) are maintained during the restoration process.

5. Software Tools:

– 2D Restoration: Commonly used for cross-sections, allowing geologists to restore profiles of folded or faulted terrains.

– 3D Restoration: Involves restoring volumes of rock in three dimensions, which is more complex but essential for understanding large-scale structures.

Applications of Structural Restoration

1. Hydrocarbon Exploration:

– Trap Integrity: Assessing whether faults or folds have remained sealed over geological time, preserving hydrocarbon accumulations.

– Migration Pathways: Understanding how deformation has influenced the pathways for hydrocarbon migration and accumulation.

2. Geohazard Assessment:

– Landslide and Fault Risk: Evaluating the potential for future deformation, including the reactivation of faults or the stability of slopes.

– Seismic Hazard Analysis: Understanding the history of fault movement to assess seismic risk in tectonically active areas.

3. Mineral Exploration:

– Vein and Orebody Formation: Reconstructing deformation history to understand the formation and distribution of mineral deposits, particularly in structurally controlled settings.

– Structural Controls: Identifying structural traps or conduits that may control the localization of mineralization.

4. Academic Research:

– Tectonic Evolution: Studying the tectonic evolution of mountain belts, rift basins, and other large-scale structures.

– Paleotectonic Models: Developing models of past tectonic regimes and plate movements based on restored geological structures.

Challenges in Structural Restoration

1. Complex Geology:

– Multiple Deformation Phases: Areas that have experienced multiple phases of deformation (e.g., folding, faulting, reactivation) are particularly challenging to restore.

– Unconformities: Gaps in the stratigraphic record (unconformities) complicate the restoration process, as they represent periods of erosion or non-deposition.

2. Data Limitations:

– Incomplete Data: Limited or poor-quality seismic, well, or outcrop data can lead to uncertainties in the restoration.

– Resolution Issues: The resolution of geological data, particularly in subsurface studies, can limit the accuracy of restorations.

3. Restoration Assumptions:

– Simplifying Assumptions: Simplifications in restoration methods (e.g., assuming planar faults or uniform layer thickness) can introduce errors.

– Non-Rigid Deformation: Dealing with non-rigid deformation (e.g., ductile flow) is complex and often requires advanced modeling techniques.

4. Computational Complexity:

– 3D Restoration Challenges: While 2D restorations are relatively straightforward, 3D restorations require complex calculations and significant computational power.

– Modeling Nonlinearity: Nonlinear deformation processes, such as viscoelastic behavior, are challenging to model accurately.

Conclusion

Structural restoration is a vital tool in geology, providing insights into the deformation history, validating geological models, and aiding in resource exploration. Despite the challenges, advancements in technology and modeling techniques continue to improve the accuracy and utility of structural restorations, making it an indispensable part of geological studies and practical applications in hydrocarbon and mineral exploration.