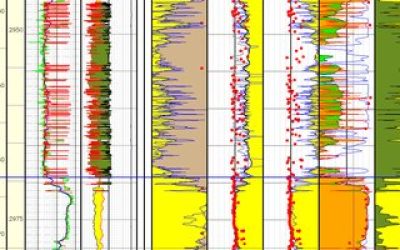

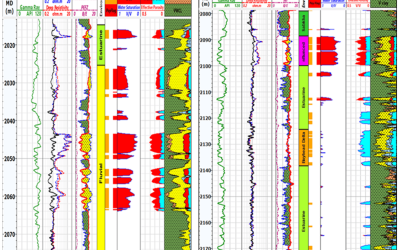

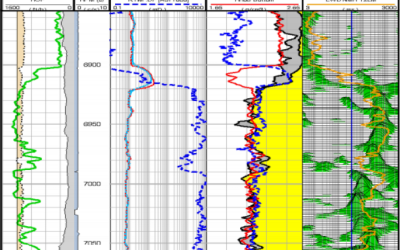

Syntillica offers expert petrophysical analysis for exploration, appraisal and development wells including desktop studies, reviews and real-time interpretation.

Interpretation of petrophysical data can have a profound impact on the volume of hydrocarbons in place and a thorough understanding of the logs is vital. Not only individual log interpretations but the combination of multiple logs in the context of reservoir type (e.g. clastic/carbonate) requires experience and a rigorous approach.

Syntillica can provide individual interpretations to correlation and analysis of log data which can be built into an audited database of wells. This can be combined with other subsurface data from geophysics, geology and geomechanics to models useful for dynamic modelling and drilling.

Porosity and Permeability Analysis are fundamental aspects of reservoir characterization in petroleum geology and hydrogeology. These properties determine the ability of a reservoir rock to store and transmit fluids, such as oil, gas, or water. Understanding porosity and permeability is crucial for evaluating a reservoir’s potential productivity and designing appropriate extraction or management strategies.

Porosity Analysis

Porosity is the measure of the void spaces (pores) within a rock and is usually expressed as a percentage of the total rock volume. It indicates how much fluid a rock can potentially hold.

Types of Porosity

1. Primary Porosity:

– Intergranular Porosity: The space between grains in sedimentary rocks, such as sandstones, typically formed during deposition.

– Intercrystalline Porosity: Found in crystalline rocks, such as carbonates, where porosity exists between the crystals.

2. Secondary Porosity:

– Fracture Porosity: Porosity that results from the presence of fractures or cracks in the rock.

– Vuggy Porosity: Large voids or cavities in carbonate rocks formed due to dissolution or other diagenetic processes.

3. Effective Porosity:

– The interconnected pore space that contributes to fluid flow. Effective porosity excludes isolated pores that do not contribute to fluid movement.

4. Total Porosity:

– The total volume of pore space in a rock, including both connected and unconnected pores.

Measuring Porosity

1. Laboratory Methods:

– Core Analysis: Porosity is measured directly on rock samples (cores) extracted from the reservoir. Methods include helium porosimetry, where helium gas is used to fill the pore spaces, and gravimetric methods, which involve calculating the pore volume from the weight difference of the rock when dry and when saturated with a fluid.

– Thin Section Analysis: Microscopic examination of thin rock sections can reveal the porosity type and distribution, helping to identify the porosity’s origin.

2. Well Logging:

– Density Logs: Measure the bulk density of the formation, which can be used to estimate porosity based on the difference between the rock matrix and fluid densities.

– Neutron Logs: Sensitive to hydrogen atoms, primarily found in water and hydrocarbons within the pore spaces, neutron logs provide a porosity estimate.

– Sonic Logs: Measure the travel time of sound waves through the formation. The speed of sound varies with the porosity of the rock, allowing for porosity estimation.

Permeability Analysis

Permeability is a measure of a rock’s ability to transmit fluids through its pore spaces and is typically measured in millidarcies (mD) or darcies (D).

Types of Permeability

1. Absolute Permeability:

– The permeability of a rock when it is fully saturated with a single fluid. It represents the rock’s intrinsic ability to transmit that fluid.

2. Effective Permeability:

– The permeability of a rock to one fluid phase in the presence of other fluid phases. For example, the permeability to oil in a reservoir containing both oil and water.

3. Relative Permeability:

– The ratio of effective permeability of a fluid at a given saturation to the absolute permeability of the rock. It describes how permeability changes as the saturation of different fluids in the rock changes.

Factors Affecting Permeability

1. Pore Size and Connectivity:

– Larger, well-connected pores generally result in higher permeability. Poorly connected or isolated pores reduce permeability.

2. Grain Size and Sorting:

– Well-sorted rocks with uniform grain sizes typically have higher permeability than poorly sorted rocks.

3. Cementation:

– The presence of cementing material between grains can reduce pore space and connectivity, lowering permeability.

4. Fractures:

– Fractures can significantly enhance permeability by providing additional pathways for fluid flow, particularly in otherwise low-permeability rocks like shales.

Measuring Permeability

1. Laboratory Methods:

– Core Analysis: Permeability is measured directly on core samples using a permeameter, which forces a fluid (typically gas or liquid) through the core and measures the flow rate under controlled pressure conditions.

– Pulse-Decay Permeability: Particularly useful for very low-permeability rocks (e.g., shales), this method involves applying a pressure pulse and observing the decay over time.

2. Field Methods:

– Drill Stem Tests (DST): Measure formation pressure and fluid flow rates in the wellbore, providing an estimate of in-situ permeability.

– Well Testing: Involves producing fluid from the well at a controlled rate and analyzing the pressure response to estimate permeability and reservoir properties.

3. Well Logging:

– Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Logging: Provides information about pore size distribution, which can be used to estimate permeability. NMR tools measure the relaxation times of hydrogen nuclei, which are related to the size and connectivity of pores.

Porosity and Permeability Relationship

– Reservoir Quality:

– High porosity and permeability generally indicate good reservoir quality, meaning the rock can store and transmit significant amounts of hydrocarbons.

– However, high porosity does not always correlate with high permeability. For instance, clay-rich rocks may have high porosity but low permeability due to the small pore throats and poor connectivity.

– Petrophysical Models:

– Various models, such as the Kozeny-Carman equation, relate porosity and permeability mathematically. These models help predict permeability based on porosity and other rock properties like pore size distribution.

Applications in Reservoir Characterization

1. Reservoir Estimation:

– Porosity and permeability data are used to estimate the volume of recoverable hydrocarbons and predict production rates.

2. Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR):

– Understanding the distribution of porosity and permeability within the reservoir is crucial for designing EOR techniques, such as water flooding or gas injection, which rely on fluid movement through the reservoir.

3. Reservoir Simulation:

– Accurate porosity and permeability values are essential inputs for reservoir simulation models that predict fluid flow and pressure changes over time, helping to optimize production strategies.

4. Reservoir Heterogeneity:

– The spatial variability of porosity and permeability within a reservoir affects fluid flow patterns and recovery efficiency. Mapping these properties helps identify high-permeability zones (sweet spots) and areas that may require different production strategies.

Challenges in Porosity and Permeability Analysis

1. Scale Dependency:

– Measurements of porosity and permeability can vary depending on the scale of observation (e.g., core, log, or field scale). Integrating data from different scales is necessary for accurate reservoir characterization.

2. Anisotropy:

– Rocks may exhibit different permeability in different directions due to layering, fracturing, or other geological features. Accounting for anisotropy is crucial for accurate flow predictions.

3. Heterogeneity:

– Reservoir rocks are often heterogeneous, with significant variability in porosity and permeability. This heterogeneity can complicate the prediction of reservoir performance and requires sophisticated modeling approaches.

Conclusion

Porosity and permeability analysis is essential for understanding a reservoir’s storage and flow characteristics. By accurately measuring and modeling these properties, geoscientists and engineers can better predict reservoir behavior, optimize recovery strategies, and maximize the economic return from hydrocarbon reservoirs. These analyses also play a critical role in other fields, such as groundwater management, carbon sequestration, and geothermal energy production.

Thin Bed Analysis is a specialized aspect of reservoir characterization that focuses on identifying and evaluating thinly bedded reservoirs. These beds are typically too thin to be accurately resolved by conventional seismic or well-logging tools, yet they can contribute significantly to the hydrocarbon reserves in a reservoir. Accurate thin bed analysis is crucial for optimizing hydrocarbon recovery from such reservoirs.

Challenges of Thin Bed Analysis

1. Resolution Limits:

– Conventional seismic and logging tools have limited vertical resolution. For seismic data, the resolution is governed by the wavelength of the seismic waves, while for logging tools, it depends on the design and response time of the sensors. Thin beds often fall below these resolution limits, leading to issues such as “tuning” where the reflections from the top and bottom of the bed interfere, distorting the true thickness and properties of the bed.

2. Tuning Effect:

– When the thickness of a bed is less than a quarter of the seismic wavelength, the reflected waves from the top and bottom of the bed interfere with each other, altering the amplitude and phase of the seismic signal. This effect can make thin beds appear thicker or thinner than they are or even cause them to be missed entirely.

3. Log Interpretation:

– Well logs, such as gamma ray or resistivity logs, may average the properties of thin beds with those of adjacent layers, leading to inaccurate readings of bed properties like porosity, permeability, or fluid content.

Techniques for Thin Bed Analysis

1. High-Resolution Logging Tools:

– Micro-resistivity Imaging Tools: These tools provide high-resolution images of the borehole wall, which can reveal thin beds that are not detected by conventional logging tools.

– Dipmeter Logs: These logs can help identify the orientation and thickness of thin beds by analyzing the variation in resistivity measurements around the borehole.

2. Seismic Inversion:

– Model-Based Inversion: Converts seismic data into a detailed impedance model of the subsurface. Thin beds, which may not be visible on conventional seismic sections, can sometimes be detected through variations in impedance that correspond to changes in lithology or fluid content.

– Sparse Spike Inversion: Focuses on reconstructing the subsurface reflectivity with higher resolution, potentially resolving thin beds that conventional inversion techniques might miss.

3. Spectral Decomposition:

– This technique decomposes seismic data into different frequency components. Higher frequencies are more sensitive to thin beds, and analyzing the frequency content of seismic data can help identify beds that are thinner than the conventional resolution limit.

4. Advanced Seismic Attributes:

– Instantaneous Frequency and Amplitude: These attributes can be used to enhance the detection of thin beds by highlighting subtle changes in the seismic signal that are associated with these layers.

– Coherence and Similarity Attributes: These can help in identifying discontinuities or subtle changes in the seismic data that might indicate the presence of thin beds.

5. Thin Bed Analysis Logs:

– High-Resolution Spectral Gamma Ray Logs: These provide more detailed measurements of the natural radioactivity of the formation, allowing for better identification of thin beds, especially in clastic sequences where gamma ray response can differentiate between shale and sandstone.

6. Rock Physics Modeling:

– Incorporating rock physics models that account for the effects of thin beds on seismic responses can improve the interpretation of seismic data. These models can simulate how thin beds would affect the seismic wavelet and help in calibrating the interpretation of seismic inversion results.

7. Multiscale Modeling:

– Combining data from different scales (core, log, seismic) to create a more detailed model of the reservoir. By integrating high-resolution data from cores or advanced logging tools with seismic data, it is possible to better characterize thin beds and their impact on reservoir properties.

Applications of Thin Bed Analysis

1. Hydrocarbon Quantification:

– Thin bed reservoirs can contain significant hydrocarbon volumes, but conventional methods might underestimate this potential. Thin bed analysis helps in accurately quantifying these resources.

2. Enhanced Reservoir Characterization:

– In fields where thin beds are prevalent, such as deepwater turbidite reservoirs or fluvial-deltaic environments, detailed thin bed analysis is critical for understanding reservoir architecture and connectivity.

3. Optimizing Well Placement and Completion:

– By identifying thin beds with good reservoir properties, operators can optimize well trajectories to maximize contact with productive intervals and design completions that effectively drain these zones.

4. Enhanced Recovery Techniques:

– Thin bed analysis can inform the design of enhanced oil recovery (EOR) methods, ensuring that these techniques are applied effectively to thinly bedded reservoirs.

Case Studies and Examples

– Turbidite Systems: Thin beds often occur in turbidite systems where sand layers are interbedded with shales. Seismic inversion and high-resolution logs are particularly useful for identifying these thin, often high-quality reservoir sands.

– Carbonate Reservoirs: In carbonate settings, thin beds can represent variations in depositional environment or diagenetic alterations. Advanced logging and seismic techniques are required to map these thin beds accurately.

Conclusion

Thin bed analysis is a critical aspect of reservoir evaluation in many geological settings. By utilizing advanced seismic and logging techniques, integrating multiple data sources, and applying detailed rock physics models, geoscientists can better resolve and characterize thin beds, leading to more accurate reservoir models and improved hydrocarbon recovery.

Saturation Height Functions are critical tools in reservoir characterization that describe the relationship between fluid saturation (typically water saturation) and height above the free water level (FWL) in a reservoir. These functions are used to predict the distribution of fluids (oil, gas, and water) in the reservoir, which is essential for estimating hydrocarbon volumes, planning development strategies, and optimizing production.

Importance of Saturation Height Functions

1. Fluid Distribution Prediction:

– Saturation height functions allow for the prediction of how water saturation changes with depth in a reservoir. This is crucial for understanding the extent of the hydrocarbon column and determining the transition zone between hydrocarbon and water-bearing portions of the reservoir.

2. Reservoir Modeling:

– These functions are integral to static reservoir models, where they are used to populate water saturation in grid cells based on their height above the FWL. This ensures a realistic distribution of fluids in the reservoir model, which is vital for accurate reserve estimation and flow simulation.

3. Well Planning and Placement:

– Understanding the saturation profile helps in placing wells optimally within the hydrocarbon column to maximize production and minimize water cut.

Conceptual Basis

The distribution of fluids within a reservoir is governed by capillary pressure, which is the difference in pressure across the interface of two immiscible fluids, such as oil and water or gas and water. Capillary pressure is a function of the pore size, fluid properties, and the height above the FWL.

– Free Water Level (FWL): The depth in the reservoir where the capillary pressure is zero, and the reservoir is fully saturated with water.

– Transition Zone: The interval above the FWL where water saturation gradually decreases, and hydrocarbon saturation increases. The thickness of this zone depends on factors such as pore size distribution, rock wettability, and reservoir heterogeneity.

Types of Saturation Height Functions

1. Empirical Functions:

– Leverett J-Function: A widely used empirical model that normalizes capillary pressure data across different rock types and fluid systems. The J-function relates capillary pressure to porosity and permeability, allowing for a generalized approach to saturation height functions.

– Log-Linear Models: These models assume a logarithmic relationship between water saturation and height above FWL, often used when data is sparse or when a simple model is sufficient for the reservoir.

2. Core-Derived Capillary Pressure Data:

– Mercury Injection Capillary Pressure (MICP): Laboratory measurements on core samples that provide detailed capillary pressure curves, which can be converted into saturation height functions by integrating the height above FWL and considering reservoir-specific fluid properties.

– Porous Plate Method: This method measures capillary pressure under reservoir conditions (e.g., using live fluids and at reservoir temperature) and is often considered more representative of in-situ conditions than MICP.

3. Petrophysical Models:

– These models derive saturation height functions by correlating log-derived properties (e.g., porosity, permeability, and resistivity) with fluid saturations, often using core data as a calibration point.

Development of Saturation Height Functions

1. Data Collection:

– Gather core data, including capillary pressure measurements, porosity, permeability, and lithological information. Well log data, such as resistivity and porosity logs, are also essential.

– Pressure data and fluid contacts (e.g., oil-water contact (OWC), gas-water contact (GWC)) help define the FWL and the extent of the hydrocarbon column.

2. Data Analysis:

– Analyze core-derived capillary pressure curves to determine the relationship between capillary pressure, fluid saturation, and height above the FWL.

– Normalize capillary pressure data using techniques like the J-function to develop a generalized model that can be applied across different reservoir zones.

3. Model Selection and Calibration:

– Choose an appropriate saturation height function model based on the reservoir’s geological setting and available data. For heterogeneous reservoirs, multiple models may be required to account for variations in rock properties.

– Calibrate the model using well log data, production history, and any available saturation data from pressure cores or fluid samples. Ensure that the model accurately predicts saturation at known depths above the FWL.

4. Integration into Reservoir Models:

– Implement the saturation height function in the reservoir model, assigning water saturations to grid cells based on their height above the FWL and local rock properties.

– Validate the model by comparing predicted fluid distributions with well test results, production data, and any additional saturation measurements.

Applications of Saturation Height Functions

1. Hydrocarbon Volume Estimation:

– By accurately predicting water saturation at different depths, saturation height functions help determine the net pay thickness and hydrocarbon pore volume, which are critical for reserve estimation.

2. Reservoir Simulation:

– In dynamic reservoir simulations, saturation height functions provide initial fluid distributions, influencing the simulation of fluid flow and pressure changes over time.

3. Water Cut Prediction:

– Understanding the saturation profile helps predict when and where water breakthrough might occur, which is essential for planning production strategies and managing water cut.

4. Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR):

– Saturation height functions can inform EOR strategies by identifying zones with residual oil saturation that could be targeted for recovery using techniques such as water flooding or gas injection.

5. Uncertainty Analysis:

– In fields with complex geology or sparse data, multiple saturation height functions may be used in a probabilistic framework to assess the uncertainty in fluid distributions and reserve estimates.

Challenges in Saturation Height Function Development

1. Data Quality and Availability:

– In some cases, core data may be limited or absent, requiring reliance on well logs or analog data, which can introduce uncertainty into the saturation height function.

2. Heterogeneity:

– Reservoirs with significant heterogeneity, such as varying lithologies or complex diagenetic histories, may require multiple saturation height functions to accurately represent different zones.

3. Capillary Pressure Variations:

– Variations in capillary pressure due to changes in rock properties or fluid composition across the reservoir can complicate the development of a single, universal saturation height function.

Conclusion

Saturation height functions are vital for accurate reservoir characterization, fluid distribution prediction, and hydrocarbon volume estimation. Developing these functions requires a careful integration of core data, well logs, and petrophysical models, tailored to the specific characteristics of the reservoir. Despite the challenges, a well-calibrated saturation height function can significantly enhance the understanding of a reservoir, leading to more effective reservoir management and optimization of hydrocarbon recovery.

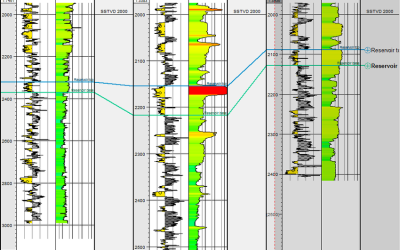

Formation Tops Correlation is a fundamental process in subsurface geology, particularly in the exploration and development of oil and gas reservoirs. It involves correlating geological formations across multiple wells or seismic sections to understand the subsurface geology, including the spatial distribution of rock units, their thickness, and their continuity. This process is critical for building accurate geological models, planning drilling programs, and optimizing reservoir development strategies.

Importance of Formation Tops Correlation

1. Geological Model Building:

– Correlating formation tops across a field helps in constructing a 3D geological model, which is essential for understanding the subsurface structure and stratigraphy.

2. Reservoir Characterization:

– Accurate correlation allows for the identification of reservoir units and non-reservoir units, aiding in the delineation of productive zones and the estimation of hydrocarbon volumes.

3. Well Planning:

– By understanding the spatial distribution of formations, geologists and engineers can plan well trajectories to target specific formations, avoid drilling hazards, and maximize hydrocarbon recovery.

4. Stratigraphic and Structural Interpretation:

– Formation tops correlation provides insights into the depositional environment, structural deformations (such as faulting or folding), and lateral facies changes, which are crucial for interpreting the geological history of an area.

Steps in Formation Tops Correlation

1. Data Collection:

– Well Logs: Collect well log data (e.g., gamma ray, resistivity, sonic, and density logs) from multiple wells. These logs are used to identify formation tops based on changes in rock properties.

– Core Data: Core samples, if available, provide direct information on lithology, which can help in confirming the log-derived formation tops.

– Seismic Data: Integrate seismic data to correlate tops across larger distances where well control is sparse. Seismic horizons can serve as guides for correlation.

2. Identifying Formation Tops:

– Log Signatures: Identify key formation tops by recognizing characteristic log responses (e.g., a sharp increase in gamma ray for shale or a decrease in density for sandstone).

– Marker Beds: Look for distinctive marker beds that are easily recognizable across multiple wells. These beds often have unique log signatures and can serve as reference points for correlation.

– Fossil Content and Biostratigraphy: In some cases, biostratigraphic data, such as the presence of specific fossils, can help identify and correlate formation tops.

3. Correlation Process:

– Vertical Correlation: Start by correlating formation tops vertically within a single well, ensuring that each top is correctly identified based on log signatures and core data.

– Lateral Correlation: Extend the correlation laterally to other wells. Look for continuity in log signatures and marker beds across wells. This process may involve shifting tops slightly in different wells to account for structural dip or stratigraphic thickness variations.

– Structural Adjustments: Consider structural features such as faults, folds, or unconformities that may cause breaks or displacements in the formation tops. Adjust the correlation to account for these features.

4. Cross-Section Construction:

– Create geological cross-sections by connecting correlated formation tops between wells. These cross-sections visualize the spatial relationships between formations and highlight structural and stratigraphic features.

5. Quality Control:

– Validate the correlation by checking for consistency with known geological features and seismic data. Discrepancies should be investigated, and the correlation adjusted as necessary.

– Perform a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of uncertain tops on the overall geological model.

Tools and Techniques

1. Well Correlation Software:

– Specialized software (e.g., Petrel, GeoGraphix, Petra) is used to visualize well logs and perform formation tops correlation. These tools often include features for creating cross-sections, mapping formation tops, and integrating seismic data.

2. Seismic Interpretation:

– Seismic data can be used to identify key horizons and faults that influence the distribution of formation tops. Seismic-to-well ties ensure that seismic horizons are accurately correlated with well data.

3. Biostratigraphy and Chronostratigraphy:

– The integration of biostratigraphic data allows for the correlation of formation tops based on the age of the rock units, providing a time-based framework for correlation.

4. Multi-Well Cross-Sections:

– Constructing cross-sections across multiple wells is a powerful technique for visualizing formation correlations and identifying any discrepancies in the correlation.

Applications of Formation Tops Correlation

1. Reservoir Delineation:

– By correlating formation tops, geoscientists can delineate the extent and thickness of reservoir units, which is crucial for reserve estimation and field development planning.

2. Stratigraphic Traps Identification:

– Correlating tops can reveal stratigraphic traps where hydrocarbons may be trapped due to changes in facies or unconformities.

3. Fault Block Mapping:

– Correlation across faulted reservoirs helps in mapping fault blocks and understanding the distribution of reservoirs and non-reservoir rocks within these blocks.

4. Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction:

– Correlating formation tops in conjunction with sedimentological and paleontological data helps reconstruct past depositional environments and understand the geological history of the basin.

Challenges in Formation Tops Correlation

1. Lateral Variability:

– In some depositional environments, such as fluvial or deltaic systems, significant lateral variability in lithology can complicate the correlation of formation tops.

2. Data Gaps:

– Sparse well control or poor-quality data can lead to uncertainties in correlation. Integrating additional data sources, such as seismic or outcrop data, can help mitigate these challenges.

3. Structural Complexity:

– In structurally complex areas with multiple faults, folds, or unconformities, accurately correlating formation tops can be challenging and requires careful structural interpretation.

4. Diagenetic Overprints:

– Diagenetic processes, such as cementation or dissolution, can alter the original rock properties, making it difficult to identify formation tops based solely on log data.

Conclusion

Formation tops correlation is a critical step in geological modeling, reservoir characterization, and well planning. It requires careful integration of well logs, core data, seismic interpretation, and geological knowledge to accurately map the subsurface and understand the distribution of rock units. Despite the challenges, successful formation tops correlation provides a robust framework for reservoir development and management, ultimately leading to more efficient and effective hydrocarbon recovery.

Rock Typing is a crucial aspect of reservoir characterization that involves categorizing rock units based on their petrophysical properties, such as porosity, permeability, and fluid saturation. These rock types, often referred to as “flow units” or “reservoir rock types,” are used to understand and model the distribution of reservoir quality across a field, which is essential for estimating reserves, planning development strategies, and optimizing production.

Importance of Petrophysical Rock Typing

1. Reservoir Characterization:

– Rock typing helps in identifying different reservoir quality zones, which is critical for understanding heterogeneity within the reservoir. This, in turn, influences fluid flow and recovery efficiency.

2. Geological Modeling:

– Petrophysical rock types are used to build static reservoir models, where each type represents a unique combination of porosity, permeability, and saturation characteristics. These models are foundational for dynamic simulation and reserve estimation.

3. Well Planning and Production Optimization:

– By identifying and mapping petrophysical rock types, engineers can optimize well placement, completion strategies, and production techniques to maximize hydrocarbon recovery.

Factors Influencing Rock Typing

1. Lithology:

– The mineral composition and grain size of the rock significantly influence its petrophysical properties. For example, sandstone, limestone, and shale each have distinct porosity and permeability characteristics.

2. Diagenesis:

– Post-depositional processes, such as cementation, dissolution, or recrystallization, can alter the original petrophysical properties of the rock, creating additional variability within the same lithology.

3. Depositional Environment:

– The depositional environment (e.g., fluvial, deltaic, marine) dictates the initial distribution of grain sizes, sorting, and sedimentary structures, which in turn affect porosity and permeability.

4. Pore Structure and Connectivity:

– The size, shape, and connectivity of the pores and pore throats are crucial in determining a rock’s ability to store and transmit fluids. Rocks with similar porosities can have vastly different permeabilities based on pore structure.

Rock Typing Methodologies

1. Core-Based Rock Typing:

– Laboratory Measurements: Direct measurements of porosity, permeability, and capillary pressure on core samples are used to define rock types. Special core analysis (SCAL) data, such as relative permeability and wettability, further refine these classifications.

– Thin Section Analysis: Microscopic examination of thin sections provides insights into the grain size, sorting, cementation, and pore structure, which are critical for defining rock types.

2. Log-Based Rock Typing:

– Porosity-Permeability Crossplots: Log-derived porosity and permeability data are plotted to identify clusters or trends that correspond to different rock types.

– Electrofacies Analysis: Using well logs such as gamma ray, neutron porosity, density, and resistivity, electrofacies (log-derived rock types) are identified using statistical or machine learning methods. This approach categorizes rock types based on their log responses rather than direct petrophysical measurements.

– Multivariate Analysis: Techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) or cluster analysis are applied to log data to identify and classify rock types.

3. Capillary Pressure and Flow Unit Analysis:

– Winland R35 Method: This method uses capillary pressure data to classify rocks based on their pore throat sizes, which are related to permeability and reservoir quality.

– Flow Zone Indicator (FZI): FZI is a dimensionless number that combines porosity and permeability to classify rock types based on their flow characteristics. Rocks with similar FZI values are grouped into the same rock type.

4. Rock Typing in Carbonate Reservoirs:

– Carbonate reservoirs often exhibit more complex pore structures compared to clastics, making rock typing challenging. Techniques such as dual porosity-permeability models and vuggy porosity classification are commonly used in carbonate reservoirs.

5. Integrated Rock Typing:

– Core-Log-Seismic Integration: Combining core data, well logs, and seismic attributes provides a more comprehensive rock typing framework. Seismic attributes can be used to extend rock types beyond well control.

– Machine Learning Approaches: Advanced machine learning techniques, such as supervised learning, are increasingly used to classify rock types by training algorithms on a combination of core, log, and seismic data.

Applications of Petrophysical Rock Typing

1. Reservoir Zonation:

– Rock typing enables the division of the reservoir into zones with distinct petrophysical properties, aiding in the identification of high-quality reservoir zones and barriers to flow.

2. Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR):

– Understanding the distribution of rock types helps in designing and implementing EOR strategies. For example, knowing the location of high-permeability channels or low-permeability barriers can optimize injection patterns.

3. Waterflooding Optimization:

– Rock typing assists in predicting the movement of water during waterflooding, helping to minimize water production and maximize oil recovery.

4. Dynamic Reservoir Simulation:

– Accurate rock typing ensures that the static model realistically represents the reservoir’s flow properties, leading to more reliable dynamic simulations and production forecasts.

5. Field Development Planning:

– Rock typing guides the selection of well locations, completion intervals, and production strategies that align with the distribution of reservoir quality.

Challenges in Petrophysical Rock Typing

1. Data Quality and Availability:

– In some reservoirs, especially those with sparse well control, limited core data or poor-quality logs can introduce uncertainties in rock typing.

2. Heterogeneity:

– Reservoirs with significant heterogeneity, such as those in complex depositional environments or with extensive diagenetic alterations, can present challenges in defining consistent rock types.

3. Scale Issues:

– Petrophysical properties can vary across different scales, from core plugs to reservoir scale. Scaling these properties accurately for rock typing is often challenging.

4. Carbonate Reservoirs:

– The complexity of carbonate reservoirs, with their wide range of pore types and diagenetic alterations, makes rock typing particularly challenging.

Conclusion

Rock typing is a critical component of reservoir characterization, providing the foundation for understanding the distribution and quality of reservoir rocks. By integrating core data, well logs, and advanced analytical techniques, geoscientists and engineers can classify rock types that accurately reflect the reservoir’s petrophysical properties. This process plays a crucial role in building reliable geological models, optimizing field development, and enhancing hydrocarbon recovery. Despite the challenges, ongoing advancements in technology and methodologies continue to improve the accuracy and utility of petrophysical rock typing in the oil and gas industry.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) is a powerful and non-destructive technique widely used in petrophysics and reservoir characterization to assess the properties of subsurface rock formations, particularly their porosity, permeability, and fluid content. NMR measurements are typically obtained through logging tools run in the borehole, providing valuable insights into the reservoir’s capacity to store and transmit fluids.

Fundamental Principles of NMR

NMR operates based on the interaction between the magnetic moments of atomic nuclei (primarily hydrogen nuclei in water and hydrocarbons) and an external magnetic field. When placed in a magnetic field, these nuclei align with the field. A radiofrequency pulse is then applied, perturbing this alignment. As the nuclei return to their original alignment (a process called relaxation), they emit a signal that can be measured and analyzed.

The two primary relaxation times measured in NMR are:

1. T1 (Longitudinal Relaxation Time): This is the time it takes for the nuclear magnetization to return to its equilibrium state along the direction of the magnetic field after the perturbation.

2. T2 (Transverse Relaxation Time): This is the time it takes for the nuclear magnetization to dephase in the plane perpendicular to the magnetic field after the perturbation.

Applications of NMR in Reservoir Characterization

1. Porosity Determination:

– NMR is highly effective in measuring porosity because the signal amplitude is directly proportional to the number of hydrogen atoms in the pore fluids. It provides total porosity, including both free and bound fluids, which is more comprehensive than traditional methods like density or neutron logs.

2. Permeability Estimation:

– Although NMR does not measure permeability directly, it provides an estimate based on the distribution of T2 relaxation times. The T2 distribution is related to pore size, and since larger pores generally correlate with higher permeability, this distribution can be used to infer permeability. Models like the Schlumberger-Doll Research (SDR) model and Coates-Timur model are commonly used for this purpose.

3. Fluid Typing and Saturation:

– NMR can distinguish between different types of fluids (e.g., water, oil, gas) based on their relaxation times. Water typically has a shorter T2 relaxation time than oil or gas due to its stronger interaction with the pore surfaces. This allows for the determination of fluid saturation and the identification of free and bound water volumes.

4. Pore Size Distribution:

– The T2 distribution provided by NMR correlates with the distribution of pore sizes within the rock. Smaller pores cause shorter T2 times, while larger pores result in longer T2 times. This information is crucial for understanding the rock’s storage and flow characteristics.

5. **Bound vs. Free Fluid Volume:**

– NMR can differentiate between bound fluids (fluids in small pores or tightly bound to the rock matrix) and free fluids (fluids in larger pores that can move freely). This differentiation is essential for calculating effective porosity and determining producible hydrocarbons.

6. Shale and Clay Volume Analysis:

– In shaly or clay-rich formations, traditional porosity logs can be misleading due to the presence of bound water in the clay structure. NMR helps to accurately estimate porosity by accounting for these bound fluids, improving reservoir evaluation in complex lithologies.

7. Formation Evaluation in Unconventional Reservoirs:

– NMR is particularly useful in evaluating unconventional reservoirs, such as tight gas sands and shale formations, where traditional logging methods may not provide sufficient information due to the complex pore structures and low permeability.

NMR Logging Tools

NMR measurements are typically obtained using wireline logging tools, which are lowered into the wellbore to collect data from the surrounding formations. Common NMR logging tools include:

1. CMR (Combinable Magnetic Resonance) Tool:

– Developed by Schlumberger, this tool provides NMR measurements in combination with other logs, allowing for comprehensive formation evaluation in a single logging run.

2. MRIL (Magnetic Resonance Imaging Log) Tool:

– Developed by Halliburton, this tool offers high-resolution NMR data, including porosity, permeability estimates, and fluid identification.

3. MREX (Magnetic Resonance Explorer) Tool:

– Another tool used for advanced NMR logging, providing detailed insights into fluid types and pore size distributions.

Interpretation of NMR Data

Interpreting NMR data involves analyzing the T2 distribution and other derived parameters. Key interpretations include:

1. T2 Cutoff:

– A critical value used to differentiate between bound and free fluids. The T2 cutoff is determined based on the rock’s lithology and is essential for estimating effective porosity and movable hydrocarbon volume.

2. Porosity Partitioning:

– NMR data allows for the partitioning of porosity into total porosity, effective porosity, and clay-bound or capillary-bound water. This partitioning is vital for accurate reservoir evaluation.

3. Fluid Typing:

– By analyzing the relaxation times, NMR can help identify the types of fluids present in the reservoir. Short relaxation times typically indicate water, while longer times may suggest oil or gas.

4. Permeability Estimation:

– Permeability is estimated using the T2 distribution, often through empirical models like the SDR or Coates models. These estimates are particularly useful in reservoirs where direct permeability measurements are not available.

Advantages of NMR Logging

1. Non-Destructive and Continuous:

– NMR provides continuous measurements along the borehole without altering the formation, offering a detailed and undisturbed view of the reservoir properties.

2. Sensitive to Fluids:

– Unlike some other logging methods, NMR directly measures the properties of the fluids within the pore space, making it highly sensitive to fluid content and type.

3. Accurate Porosity Measurements:

– NMR is less affected by lithology variations than other porosity logs, making it particularly reliable in heterogeneous or complex formations.

4. Enhanced Formation Evaluation:

– The ability to differentiate between bound and free fluids, estimate permeability, and identify fluid types significantly enhances formation evaluation and reduces uncertainties in reservoir characterization.

Challenges and Limitations

1. Complex Interpretation:

– NMR data interpretation requires specialized knowledge and expertise, particularly in selecting appropriate models and cutoffs for different reservoir types.

2. Environmental Sensitivity:

– NMR measurements can be sensitive to temperature, pressure, and borehole conditions, which may affect the accuracy of the data.

3. Cost and Time:

– NMR logging is typically more expensive and time-consuming than conventional logging methods, which can be a consideration in budget-constrained projects.

4. Limited Depth of Investigation:

– NMR tools generally have a shallow depth of investigation compared to other logging tools, which may limit their effectiveness in certain formations.

Conclusion

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance is a versatile and powerful tool in the arsenal of petrophysicists and reservoir engineers, offering unique insights into the subsurface that are not easily obtainable through other methods. By providing detailed information on porosity, permeability, fluid content, and pore size distribution, NMR plays a critical role in the accurate characterization of reservoirs, particularly in complex and heterogeneous formations. Despite its challenges, the advantages of NMR in enhancing reservoir evaluation and optimizing hydrocarbon recovery make it an indispensable technique in modern petroleum exploration and production.

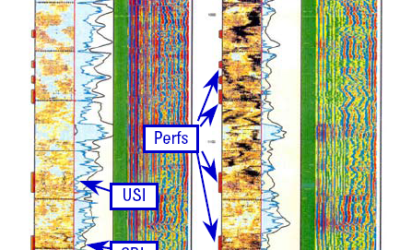

Cement Bond Log (CBL) Analysis is a crucial technique used in well logging to evaluate the integrity and quality of the cement bond between the casing and the wellbore. This analysis ensures that the cementing process has successfully isolated different formations, preventing fluid migration between zones and ensuring wellbore stability.

Purpose of Cement Bond Log Analysis

1. Evaluate Cement Integrity:

– CBL analysis helps assess whether the cement has properly bonded to the casing and the formation, ensuring the zonal isolation required to prevent fluid communication between different geological layers.

2. Identify Potential Problems:

– It identifies issues such as poor cement placement, channeling, or micro-annuli, which could lead to well integrity issues like leaks or casing corrosion.

3. Verify Well Completion:

– Before production, CBL analysis confirms that the well is properly sealed and that the cementing job has met the necessary standards for safety and operational efficiency.

4. Plan Remedial Actions:

– If the CBL indicates poor cement quality, it provides the data needed to plan remedial actions, such as squeeze cementing or re-cementing operations.

How Cement Bond Logging Works

The CBL tool typically includes an acoustic transmitter and multiple receivers placed at various distances from the transmitter. When the tool is run inside the casing, the transmitter emits an acoustic signal (usually a sonic wave) that travels through the casing, cement, and formation. The receivers measure the amplitude and travel time of the signals that return to the tool. The quality of the cement bond is inferred from these measurements:

1. High Amplitude Signal:

– A high-amplitude signal indicates poor bonding or the presence of free pipe, where the acoustic wave travels with minimal attenuation because the cement bond is weak or absent.

2. Low Amplitude Signal:

– A low-amplitude signal indicates a strong bond, where the acoustic wave is attenuated as it passes through the solid cement, indicating good cement quality and a proper bond.

3. Variable Density Log (VDL):

– The VDL is a secondary output of the CBL tool, displaying the received acoustic waveforms. It provides a detailed visual representation of the cement bond quality over time, highlighting features such as channeling, micro-annuli, or the presence of gas pockets.

Key Components of CBL Analysis

1. Amplitude Log:

– The primary output, showing the amplitude of the received acoustic signals along the wellbore. Variations in amplitude help identify the presence and quality of the cement bond.

2. Travel Time:

– The time it takes for the acoustic signal to travel from the transmitter to the receiver. Changes in travel time can indicate different materials the wave is passing through, such as free pipe, bonded cement, or formation.

3. VDL Interpretation:

– The VDL provides a more detailed, qualitative analysis of the cement bond by showing the acoustic waveform. It can identify features such as:

– Solid Cement: Characterized by wavy, consistent patterns with low amplitude.

– Free Pipe: Shown as straight, high-amplitude lines with little attenuation.

– Micro-annuli or Channels: Indicated by irregular patterns or sudden changes in the waveform.

4. Segmentation and Radial Analysis:

– Some advanced CBL tools can provide segmented or radial measurements, offering a more detailed view of the cement bond around the entire circumference of the casing, identifying localized bonding issues.

Interpretation of CBL Data

1. Free Pipe Identification:

– High amplitude and fast travel time indicate free pipe with no or poor cement bonding. This is typically seen at the top of the cemented section or in cases where cement has not been effectively placed.

2. Good Bond Identification:

– Low amplitude and slower travel times indicate a good bond between the casing, cement, and formation. The VDL would show a consistent, wavy pattern indicating well-cemented sections.

3. Partial Bonding:

– Intermediate amplitude values and varying travel times may indicate partial bonding, where the cement bond is only effective in certain sections of the casing.

4. Channeling and Voids:

– Irregular patterns in the VDL and abrupt changes in amplitude may indicate channeling, voids, or other anomalies within the cement. This is a critical finding, as it can lead to fluid migration and compromise well integrity.

Applications of Cement Bond Log Analysis

1. Well Integrity Assessment:

– CBL analysis is crucial for ensuring the long-term integrity of the well by verifying the effectiveness of the cement sheath in providing zonal isolation.

2. Regulatory Compliance:

– Many jurisdictions require CBL logs as part of the documentation to demonstrate that wells meet safety and environmental standards.

3. Field Development:

– Before completing and producing a well, CBL analysis is used to confirm that the cementing job has been successful, ensuring that the well is ready for production.

4. Plug and Abandonment Operations:

– CBL logs are used during plug and abandonment operations to confirm that the cement plugs have been properly placed and provide the necessary isolation to abandon the well safely.

Challenges in Cement Bond Log Analysis

1. Casing Centralization:

– Poor centralization of the casing can lead to an uneven cement sheath, complicating the interpretation of CBL data and potentially leading to inaccurate assessments of the bond quality.

2. Environmental Factors:

– Borehole conditions, such as temperature, pressure, and the presence of drilling fluids, can affect the quality of the acoustic signal and the reliability of the CBL data.

3. Gas in Cement:

– The presence of gas within the cement can create acoustic impedance contrasts, leading to misleading high amplitudes that may falsely indicate poor bonding.

4. Tool Calibration:

– Proper calibration of the CBL tool is essential for accurate measurements. Miscalibration can lead to incorrect amplitude readings and misinterpretation of the cement bond quality.

Conclusion

Cement Bond Log Analysis is a vital tool in well integrity management, providing crucial information on the effectiveness of the cementing job. By evaluating the bond between the casing and the formation, CBL helps ensure that wells are safely and efficiently isolated, reducing the risk of fluid migration, wellbore instability, and environmental contamination. Despite its challenges, when properly executed and interpreted, CBL analysis plays a key role in the safe and effective development and operation of oil and gas wells.

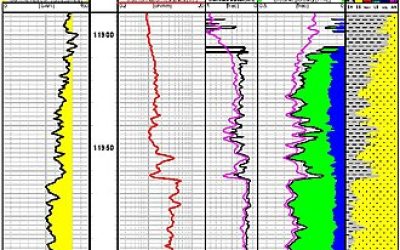

Petrophysical Quantitative Log Analysis is a systematic approach used in the oil and gas industry to evaluate the properties of subsurface formations by interpreting well log data. This analysis is crucial for understanding the reservoir’s potential to store and produce hydrocarbons, allowing for more accurate reserve estimates and well planning.

Key Objectives of Quantitative Log Analysis

1. Determine Lithology:

– Identify the rock type (e.g., sandstone, limestone, shale) by analyzing the response of various logs, such as gamma ray, density, and neutron logs.

2. Evaluate Porosity:

– Calculate the porosity of the formation, which indicates the percentage of the rock’s volume that can store fluids. Porosity logs (like neutron and density logs) are used to estimate both total and effective porosity.

3. Estimate Water Saturation:

– Determine the proportion of the pore space filled with water versus hydrocarbons using resistivity logs and applying models like Archie’s equation.

4. Calculate Hydrocarbon Saturation:

– Calculate the fraction of the pore space occupied by hydrocarbons, which is the complement of water saturation.

5. Identify Permeability Indicators:

– Estimate the rock’s ability to transmit fluids using relationships between porosity and permeability or by analyzing specific logs like NMR.

6. Determine Volume of Shale:

– Assess the proportion of shale in the formation using gamma ray or spontaneous potential (SP) logs, as shale affects the accuracy of porosity and saturation estimates.

Workflow of Petrophysical Quantitative Log Analysis

1. Data Acquisition:

– Gather well logs, core data, and other relevant geological information. The common logs used in quantitative analysis include:

– Gamma Ray Log: Measures natural radioactivity, used to differentiate between shale and clean formations.

– Resistivity Log: Measures the formation’s resistance to electrical current, used to estimate water saturation.

– Density Log: Measures electron density, correlating with bulk density and used to determine porosity.

– Neutron Log: Measures hydrogen content, also used to estimate porosity.

– Sonic Log: Measures the travel time of acoustic waves through the formation, providing porosity estimates and lithology identification.

– NMR Log: Provides detailed information on porosity, permeability, and fluid types.

2. Environmental Corrections:

– Apply corrections to log data to account for borehole effects, mud invasion, tool calibration, and other environmental factors that could distort measurements.

3. Lithology and Mineralogy Analysis:

– Determine the rock type and mineral composition using crossplots and mineral models. For example, a density-neutron crossplot can help distinguish between different types of carbonates and siliciclastics.

4. Porosity Calculation:

– Calculate porosity using one or more porosity logs (density, neutron, or sonic logs). For accurate results, correct for lithology and fluid effects:

– Density Porosity: Uses the bulk density measurement and known matrix and fluid densities.

– Neutron Porosity: Measures the hydrogen content, which correlates with porosity, but needs correction in the presence of gas or non-aqueous fluids.

– Sonic Porosity: Based on the travel time of sound waves through the formation, adjusted for lithology.

5. Volume of Shale Estimation:

– Calculate the shale volume using gamma ray, SP, or density-neutron crossplot methods. Shale volume affects porosity and saturation calculations:

– Gamma Ray Index (IGR): Used to estimate shale volume using a linear or non-linear relationship.

– Density-Neutron Crossplot: Helps to distinguish shale from clean formations and estimate shale content.

6. Water Saturation Calculation:

– Estimate water saturation using resistivity logs and Archie’s equation or its modified versions:

– Archie’s Equation:

S_w = \left(\frac{a \times R_w}{\phi^m \times R_t}\right)^{\frac{1}{n}}

Where \(S_w\) is water saturation, \(R_w\) is formation water resistivity, \(R_t\) is true resistivity, \(\phi\) is porosity, and \(a\), \(m\), and \(n\) are empirically derived constants.

– Simandoux Equation: Used in shaly sands to account for the conductivity of the shale.

– Indonesia Equation: Another model used for shaly formations, considering the conductivity of the formation water and shale.

7. Hydrocarbon Saturation Calculation:

– Calculate hydrocarbon saturation as the complement of water saturation:

S_h = 1 – S_w

– This value indicates the percentage of the pore space occupied by hydrocarbons, which is crucial for estimating recoverable reserves.

8. Permeability Estimation:

– Estimate permeability using empirical relationships with porosity (e.g., Wyllie-Rose or Coates equations) or directly from NMR logs, which provide a more direct estimate based on pore size distribution.

9. Crossplot Analysis:

– Utilize various crossplots (e.g., neutron-density, resistivity-porosity) to refine lithology interpretation, validate log-derived parameters, and identify fluid types.

10. Net Pay Calculation:

– Identify the intervals that are potentially productive by applying cutoffs for porosity, water saturation, and shale volume. These intervals represent the “net pay” zones.

Interpretation and Integration

1. Core Calibration:

– Compare and calibrate log-derived parameters with core measurements, if available, to improve accuracy. Core data provides ground truth for porosity, permeability, and saturation.

2. Formation Evaluation:

– Integrate the log analysis results with geological and geophysical data to create a comprehensive model of the reservoir. This includes identifying key reservoir zones, fluid contacts, and potential barriers to flow.

3. Uncertainty Analysis:

– Evaluate the uncertainty in the log-derived parameters due to variations in lithology, fluid properties, tool accuracy, and environmental corrections. Sensitivity analysis is often performed to understand the impact of these uncertainties on reserves estimation and well planning.

4. Reporting and Decision-Making:

– Present the quantitative analysis results in a format that supports decision-making for exploration, development, and production. This typically includes detailed log interpretations, crossplots, maps of reservoir properties, and reserve estimates.

Challenges and Considerations

1. Complex Lithologies:

– Mixed lithologies, such as laminated sands and shales or carbonates with vugs and fractures, can complicate the interpretation of log data and require advanced models or multi-mineral analysis.

2. Shaly Formations:

– The presence of shale complicates porosity and saturation calculations due to the conductive nature of clay minerals, which can affect resistivity and porosity measurements.

3. Gas Effects:

– Gas in the formation can lead to anomalies in neutron and density logs, often resulting in overestimated porosity or misinterpreted fluid types.

4. Data Quality:

– The accuracy of quantitative log analysis is highly dependent on the quality of the log data. Issues like poor tool calibration, borehole washouts, or invasion by drilling fluids can lead to errors in interpretation.

5. Calibration with Core Data:

– Where available, core data should be used to calibrate log-derived estimates of porosity, permeability, and saturation to reduce uncertainty.

Conclusion

Petrophysical Quantitative Log Analysis is a critical process in reservoir characterization, providing the quantitative data necessary to estimate reserves, plan wells, and optimize production strategies. By combining various logging tools and analytical techniques, petrophysicists can derive detailed insights into the subsurface, improving the understanding of the reservoir’s potential and guiding effective decision-making in the exploration and development of hydrocarbon resources.